(Excerpts from Ray Brandes’ definitive history of a band that shaped San Diego music. Read the full version in Che Underground’s Related Bands section.)

On October 8, 1977, Santana and Journey played to a sold-out crowd at the San Diego Sports Arena. That same night, across town at the Adams Avenue Theater, a decrepit former cinema, the Zeros, Dils and Hitmakers were making history by playing what has since come to be considered a milestone San Diego concert: the first big punk show.

On October 8, 1977, Santana and Journey played to a sold-out crowd at the San Diego Sports Arena. That same night, across town at the Adams Avenue Theater, a decrepit former cinema, the Zeros, Dils and Hitmakers were making history by playing what has since come to be considered a milestone San Diego concert: the first big punk show.

The audience was full of artists, musicians and poets, future movers and shakers who would go on to form bands, create fanzines, open independent record stores, and promote shows and galleries for decades to come. Among those in attendance were several young misfits who were drawn together by their love for early rock and roll and beat music and who would eventually change the local musical landscape as the Penetrators.

At the height of their popularity, the Penetrators were San Diego’s hometown heroes and media darlings, the local entry with the best chance to win the big-label sweepstakes. They took punk rock out of the downtown dives and brought it into suburban living rooms and car-radio speakers. In doing so they became bona fide local celebrities, selling out large arenas and hobnobbing with the Rolling Stones, Ramones and B-52s.

At the height of their popularity, the Penetrators were San Diego’s hometown heroes and media darlings, the local entry with the best chance to win the big-label sweepstakes. They took punk rock out of the downtown dives and brought it into suburban living rooms and car-radio speakers. In doing so they became bona fide local celebrities, selling out large arenas and hobnobbing with the Rolling Stones, Ramones and B-52s.

It couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more deserving group of young men. They were kind and generous with their fans; supportive of local music; friendly, gregarious and fun. Most importantly, however, they were ever conscious of their roots and grateful for the opportunity to be the rising tide that would lift the boats of all of San Diego’s bands.

Queenie

The Penetrators can trace their roots to the late ‘60s, to a group of kids who used to gather at the home of popular Emerald Junior High School English teacher John Kmak, whose sons Joel and Jeff would listen to and play along with Beatles 45s. Among the musicians who found themselves at one time or another at the Kmaks’ Grand Central Station were Scott Harrington; Steve Kelly (later of the Hitmakers); and Dan McLain, whom Joel Kmak described seeing for the first time in his living room: “He was a tall, whippet-like kid who was just beating the crap out of the drums.”

By the time they got to high school in the early ‘70s, drummer Joel Kmak; bassist Steve Kelly; Dan McLain (who had now switched to piano); and guitarists Brian Quinn and Brian Bardot were already musically out of step with their peers. The band they formed, Queenie (named for the Chuck Berry song “Little Queenie”), was far more interested in Buddy Holly, Little Richard, the Kinks, the Who, the Animals and the Stones than the progressive hard rock favored by the unwashed masses at Grossmont High School. They were led by popular ASB Vice President McLain and soft-spoken musicologist Brian Bardot, who was so obsessed with tracing the Beatles’ and Stones’ roots that “the joke was that Bardot was going to get as far back as the Big Bang and disappear,” says Kmak.

By the time they got to high school in the early ‘70s, drummer Joel Kmak; bassist Steve Kelly; Dan McLain (who had now switched to piano); and guitarists Brian Quinn and Brian Bardot were already musically out of step with their peers. The band they formed, Queenie (named for the Chuck Berry song “Little Queenie”), was far more interested in Buddy Holly, Little Richard, the Kinks, the Who, the Animals and the Stones than the progressive hard rock favored by the unwashed masses at Grossmont High School. They were led by popular ASB Vice President McLain and soft-spoken musicologist Brian Bardot, who was so obsessed with tracing the Beatles’ and Stones’ roots that “the joke was that Bardot was going to get as far back as the Big Bang and disappear,” says Kmak.

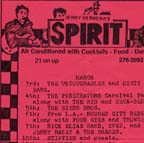

Queenie loaded Dan’s upright piano into his Ford Econoline van and traveled all over San Diego for gigs, even appearing several times at Jerry Herrera’s club JJ’s on Pacific Coast Highway. The band made sure to play obscure covers only, and often became antagonistic with the crowds who would clamor for the popular hits of the day. After playing “Bad Boy” or “Dizzy Miss Lizzy,” someone might call out for a Beatles song, Joel remembers. “Brian would shout out, ‘We just played a Beatles song, you bitch!’ We had an aggressive attitude,” says Kmak, “and when punk came along, we could totally relate to it. “

The Big Guy

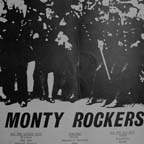

Eventually, Queenie’s plans to move to LA to record and make it big were dashed when Bardot and McLain had a bad falling-out and McLain quit the band. McLain married soon thereafter; became president of the San Diego Kinks Fan Club; and began to collect the records he would eventually use to open his own store, Monty Rockers.

It was at Monty Rockers, out on El Cajon Boulevard, west of College Avenue, that McLain took on the role of den mother to a motley little collection of brilliant, funny, creative people. He was at home in his natural habitat, conducting impromptu rock-and-roll history lessons and sharing his favorite music with the clientele. McLain was the best kind of rock-and-roll mentor, encouraging kids to start bands; create their own fanzines; and of course, buy cool records. It’s hard to imagine a more important tastemaker in the early days of the San Diego scene.

It was at Monty Rockers, out on El Cajon Boulevard, west of College Avenue, that McLain took on the role of den mother to a motley little collection of brilliant, funny, creative people. He was at home in his natural habitat, conducting impromptu rock-and-roll history lessons and sharing his favorite music with the clientele. McLain was the best kind of rock-and-roll mentor, encouraging kids to start bands; create their own fanzines; and of course, buy cool records. It’s hard to imagine a more important tastemaker in the early days of the San Diego scene.

Meanwhile, over at Monte Vista High School in Spring Valley, former drummer Scott Harrington was deciding to learn the guitar. “During my senior year I decided I wanted to play guitar like Jimi Hendrix,” says Harrington. “I soon realized that’s a bad place for a guitarist to start. I started listening to Keith Richards, and through the Stones and Beatles, Chuck Berry.” After high school, Harrington and Kmak became reacquainted at Grossmont College and played together for a year or so at Harrington’s aunt’s house, sometimes joined by former Queenie bassist Steve Kelly. “At the time (1975-1976), there were no places to play unless you were a disco or Top 40 band,” recalls Kmak. “We’d put all our shit in our cars, go to biker bars and ask if they needed a band. A lot of the bikers wouldn’t be too happy because they’d have to stop playing pool!” Harrington adds, “At the time we were into British Invasion stuff, but speeding it up, making it faster and harder. I was scouring magazines like Creem and Trouser Press for new bands to listen to. It was all about not being Styx and Fleetwood Mac.”

Then, according to Kmak, “Punk hit, and within six months it seemed like the whole world had changed. There were all these kids hanging out at Monty Rockers. Every day you’d see somebody new, and you’d think, ‘Now there’s someone else on the team!’ ” Harrington recalls: “I said to Joel, ‘There is some new stuff going on, and we really need to get with it.’ We didn’t want to get left behind in the ‘70s, so we put an ad in the paper for people who were into Beatles, Kinks, Stones.”

At the time the Hitmakers — Joseph Marc, Jeff Scott and Ron Silva — were running a nearly identical ad in the Reader citing the Beatles, Stones and Kinks as influences. Harrington answered the ad and spoke to Jeff Scott, who invited Harrington, Kelly and Kmak to a party in Oceanside. The Zeros were playing, along with an embryonic version of the Hitmakers (Silva, Marc, Jeff Scott, and Silva’s brother on drums). The Hitmakers were looking for some other members and ended up taking Steve Kelly for bass. That left a frustrated Kmak and Harrington looking for a new bass player. The solution to their problem, in the form of a tall skinny kid with a jet-black pompadour and juvenile delinquent sideburns, showed up for an audition at the Harrington practice space a few weeks later.

“Three chords and an attitude”

Chris Sullivan was born in Yonkers, N.Y., in a cross-section Italian and African-American neighborhood. He grew up in a household full of music — Johnny Cash and Duane Eddy were constantly on his older siblings’ turntable — and he started noodling with a guitar at age three. Sullivan remembers that “the lights came on for me in 1964 when the Beatles played the Ed Sullivan show.” He tried to put a band together that same week. “I went to Flagg Brothers for Beatle boots, but my parents wouldn’t let me get them,” he says. His father, who worked in elevator construction on the World Trade Center, pitched in 15 dollars to help him buy his very first electric guitar, a $40 metallic-blue Norma with four pickups. “I used to walk the streets, playing that guitar all day,” Sullivan remembers. “It was all three-chords-and-an-attitude music,” he says.

Chris Sullivan was born in Yonkers, N.Y., in a cross-section Italian and African-American neighborhood. He grew up in a household full of music — Johnny Cash and Duane Eddy were constantly on his older siblings’ turntable — and he started noodling with a guitar at age three. Sullivan remembers that “the lights came on for me in 1964 when the Beatles played the Ed Sullivan show.” He tried to put a band together that same week. “I went to Flagg Brothers for Beatle boots, but my parents wouldn’t let me get them,” he says. His father, who worked in elevator construction on the World Trade Center, pitched in 15 dollars to help him buy his very first electric guitar, a $40 metallic-blue Norma with four pickups. “I used to walk the streets, playing that guitar all day,” Sullivan remembers. “It was all three-chords-and-an-attitude music,” he says.

Sullivan’s other love was baseball — he would later be drafted by the Kansas City Royals at age 16 — but recalls a turning point occurring on his 14th birthday. “I had to choose between a Rawlings Brooks Robinson baseball glove and a wah-wah pedal,” he says. “I went with the wah-wah pedal.”

Due to his father’s poor health, the family packed up and moved to the warm climate of San Diego, where Sullivan finished his senior year at Mount Miguel High School in Spring Valley. In 1972, he was sporting an Elvis haircut and long sideburns and was listening exclusively to old blues, country and British Invasion music. “I didn’t get along with or hang out with too many people — they just didn’t know what to make of me,” Sullivan says. “But I wasn’t picked on because I had grown up in some pretty tough New York neighborhoods. I learned pretty early on to fight the leader of the group first.”

Sullivan graduated in 1973 and began attending Grossmont College, where he became acquainted with Sam Sanford, former guitarist and singer with ‘60s garage band the Gants. The two played a few military bases and frat parties in a group called Thunderbuck Ram. In early 1977 he answered the Reader ad placed by Harrington and Kmak and ended up at his first-ever music audition. “We played six or seven songs, and right away we clicked,” he recalls. “They took me aside and said, ‘We’d like to make you an offer to join our band.’ ”

Just as Sullivan, Kmak and Harrington began to amass a catalog of songs, the Hitmakers again came calling. Kmak remembers: “After a couple of months, Joseph Marc decided he wanted to switch from drums to guitar. So one night, Steve Kelly came around to my house and said, ‘Guess what? These guys want you in the band. We got a gig in Hollywood. Are you in or out?’” Kmak was admittedly starstruck with the Hitmakers, who had some big shows lined up in Los Angeles. He joined without much thought. “The first gig I played with them was at the Masque with the Germs and the Bags,” he says. “Rodney Bingenheimer was sitting at the side of the stage.”

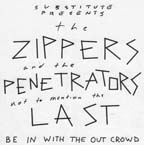

They had no drummer, and they had no singer, but Harrington and Sullivan had a band name, courtesy of Mark Williams, a high school friend of Chris’ who suggested “Rock Jetty and the Penetrators.” They once again resorted to their Reader ad. This time, however, they tried a new tactic. “We would go around to record stores like Blue Meanie and stick flyers in the bins next to cool records,” says Harrington. The flyers read: “Do You Want to Be a Penetrator?”

They had no drummer, and they had no singer, but Harrington and Sullivan had a band name, courtesy of Mark Williams, a high school friend of Chris’ who suggested “Rock Jetty and the Penetrators.” They once again resorted to their Reader ad. This time, however, they tried a new tactic. “We would go around to record stores like Blue Meanie and stick flyers in the bins next to cool records,” says Harrington. The flyers read: “Do You Want to Be a Penetrator?”

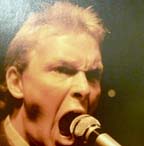

In the months that followed, word had began to circulate around town about a wild-eyed singer named Gary who fronted a band called Monotone and the Nucleoids. Harrington and Steve Kelly had seen him in line at the Ramones, taunting some jock types by dancing on the ground like a fried egg. Later, Sullivan would remember him as the fellow Elvis fan he met while camped out for tickets at the Sports Arena in 1972. Encountering Gary would be another critical moment for the band.

“We had heard about this party in La Mesa where a group called Monotone and the Nucleoids were playing,” says Sullivan. “We went there specifically to check out the singer.” According to Sullivan, Gary was “flapping around like Daffy Duck.” Harrington recalls: “The band wasn’t very good, but the singer had an energy and a personality, and we said, ‘Let’s talk to this guy and get his number.’ ” “Gary jumped on it right away,” says Sullivan. The three began rehearsing nearly every day.

Sensitive Boy

Gary Heffern’s early childhood in a Finnish orphanage was well-documented in John Caldwell’s 1957 book Children of Calamity. The youngest of eight abandoned siblings found in a barn, he was adopted and raised by a strict, conservative family in Solana Beach.

Gary Heffern’s early childhood in a Finnish orphanage was well-documented in John Caldwell’s 1957 book Children of Calamity. The youngest of eight abandoned siblings found in a barn, he was adopted and raised by a strict, conservative family in Solana Beach.

He has always been an outsider. At the height of the psychedelic era, when his classmates were growing their hair long and participating in protests against the Vietnam War, Heffern’s parents made him keep his hair short and refused to allow him to speak about the events happening overseas. His escape was music, and he says he sought out the “craziest album covers I could find.”

When Heffern was in the seventh grade at Earl Warren Junior High School, a confrontation with his parents galvanized in him a view of music as the ultimate form of rebellion. “One day I was going through the medicine cabinet at home and found a bunch of Nembutals that belonged to my mother,” he recalls. “Throughout the day I ended up taking eight of them and passed out at the dinner table. I woke up in the hospital having my stomach pumped by a doctor who also turned out to be my Boy Scout leader. It was then decided that I was no longer allowed to be a scout.”

Gary watched in horror as his parents went into his bedroom, collected about 50 of his albums, and shattered them into tiny pieces. They then burned all of the covers and inner sleeves in the fireplace. “The albums I watched burn,” says Heffern, “included the 13th Floor Elevators, the Blues Magoos, the Velvets, Love, the Monkees, the Turtles’ ‘Happy Together,’ the Mothers’ ‘Freakout’ and ‘Surrealistic Pillow’ by the Jefferson Airplane.”

In November 1968, at age 13, Heffern snuck out of his bedroom window and hitchhiked to the Hippodrome in downtown San Diego to see the Velvet Underground and the Quicksilver Messenger Service. “At the time you had to be 16 or 18 to get in, so I gave the doorman a joint to let me sneak in,” Heffern remembers. “I got to see the VU booed off the stage. I remember they were wearing suits and Beatle boots and were pissed at the audience.”

In March of the following year, Heffern saw Janis Joplin at the San Diego Sports Arena. “I think it was the first time I saw someone really emote in front of a crowd, and it mesmerized me,” he says. “I knew then — that’s who I wanted to be and what I wanted to do.”

Heffern’s family moved to Point Loma when Gary was in the ninth grade, and at Point Loma High School he continued to escape through music and drugs. “I would wake up in the mornings, smoke pot on the way to school, meet at the church across the street and get white crosses,” he says. “I would usually take anywhere from four to five daily, and then go play handball for two to four hours. At lunch I would go to the record store right down the street, and since I was always working jobs, I would buy whatever had come out that day. At this point I don’t think that I was really searching for anything musically, other than the way that albums would make me feel.”

After high school Heffern began writing songs for friends’ bands and began developing his rock and roll persona. “My style was straight-leg pants, striped shirts, Beatle boots and really old suits,” he says. “In the beginning, my attitude was just to stir shit up. I was no saint — let’s put it that way — but I also wanted to do music that would affect people.”

Another key moment in Heffern’s life came at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in April 1977. Iggy Pop was performing his last encore, a cover of Them’s “Gloria” with David Bowie on backing vocals. Heffern remembers: “I was near the front and Iggy gave me the mic … so I sang! The next night I was in the second row at the San Diego Civic Theater, and he again he handed me the mic. I knew then that I had to start a band!”

The formation of Heffern’s first band occurred under unusual circumstances, to say the least. “Right after the Iggy show, I thought up the name ‘Monotone and the Nucleoids,’ put it on a T-shirt and wore it to a show at Montezuma Hall,” laughs Heffern. “These Mexican guys in suits came up and started asking me about that band, as they had never heard of them. I told them it was my new band and asked them if they wanted to join! We exchanged info, they called me and that was that!”

The search for a drummer

With most of the band in place, the search for a drummer intensified. Countless auditions were held, but Harrington, Sullivan and Heffern knew most of them would not work out even before their gear was fully unloaded. “These guys would keep showing up with massive sets with two kick drums,” says Sullivan. “We could tell by the haircuts with most of them.” Finally, out of desperation, they approached McLain at Monty Rockers. “I asked Dan,” says Harrington, “’Look — we need a drummer. If we put a kit together, could you come out and sit in with us?’ We put this ramshackle set together, and he started playing and it sounded great.” Sullivan remembers that first practice: “Dan wasn’t a great time keeper, but he had a great feel for the drums — he had rock and roll in his soul. We all generally accepted that since he had that feel, he was only going to get better.”

With most of the band in place, the search for a drummer intensified. Countless auditions were held, but Harrington, Sullivan and Heffern knew most of them would not work out even before their gear was fully unloaded. “These guys would keep showing up with massive sets with two kick drums,” says Sullivan. “We could tell by the haircuts with most of them.” Finally, out of desperation, they approached McLain at Monty Rockers. “I asked Dan,” says Harrington, “’Look — we need a drummer. If we put a kit together, could you come out and sit in with us?’ We put this ramshackle set together, and he started playing and it sounded great.” Sullivan remembers that first practice: “Dan wasn’t a great time keeper, but he had a great feel for the drums — he had rock and roll in his soul. We all generally accepted that since he had that feel, he was only going to get better.”

The now complete Penetrators began to write their own songs and develop a set list. “Early on we were doing as many originals as possible,” Sullivan says. “I wasn’t a very good cover player,” he adds. “It was easier for me to play what I had written. So I’d start with a bass hook, Scott would help me with the chords, and then Gary would write the lyrics.” Rounding out the set were songs like ‘Do You Love Me?’ by the Contours; ‘Don’t Lie to Me’ by Chuck Berry; and some Bo Diddley, Sex Pistols, Ramones, and Kinks.

The Penetrators’ debut took place in the recreation room of the Sea Colony Inn in Ocean Beach. Soon afterwards, they played their first club gig at Abbey Road, located on the 3100 block of University Avenue in North Park. The club was originally a small discotheque, complete with disco ball and strobe lights, but in the early days of the burgeoning San Diego punk scene, Abbey Road began opening on Mondays for “New Wave Night.” It wasn’t much, but at the time it was one of the few games in town.

The Penetrators’ debut took place in the recreation room of the Sea Colony Inn in Ocean Beach. Soon afterwards, they played their first club gig at Abbey Road, located on the 3100 block of University Avenue in North Park. The club was originally a small discotheque, complete with disco ball and strobe lights, but in the early days of the burgeoning San Diego punk scene, Abbey Road began opening on Mondays for “New Wave Night.” It wasn’t much, but at the time it was one of the few games in town.

Sullivan remembers the house bouncer used to give him a hard time, calling him “John Travolta.” Harrington laughingly recalls a show in early 1978 when he, McLain and Steve Kelly, playing in a side project called The Mondellos, opened for the group X. Somehow, the Mondellos’ onstage antics were insulting to the members of X. “They thought we were mocking punk rock,” Harrington says, “and became very upset. Exene and John Doe got in a fistfight with us outside the club!”

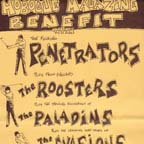

The Penetrators rapidly developed a following around town, playing house parties and shows at the North Park Lions Club; the VFW Hall in La Mesa (where the La Mesa Police showed up with their canine units); the Skeleton Club; and the San Diego Yacht Club.

Their popularity was due in large degree to their charming, unreserved personalities. They were natural public-relations representatives — friendly, outgoing and well-spoken — and it was easy to root for their success because they were such genuinely nice guys. They wanted to see other bands do well and were supportive of younger musicians and fans. Harrington, Sullivan, McLain and Heffern worked every room of every party they attended, and Chris, as de facto leader of the band, typed press releases and invitations to members of the local press. “My approach,” says Sullivan, “was the same approach I took with bullies. I pitched us to the very top. And one by one, these guys started showing up for our shows.”

Untamed Youth

In the summer of 1978, the Penetrators arrived at a small eight-track studio Harrington had found in Pasadena, Calif., called Hound Dog Studios. It was the first experience for any of them in a real recording studio. Sullivan remembers, “I was really impressed. They gave us books of matches with pictures of hound dogs playing cards — I was hooked right away. When we started to record, we were so excited that we were playing extremely fast.”

The band’s exuberance is evident from the opening drum beats of “Untamed Youth,” the first of three songs they recorded that day. The engineer shouts into the microphone, “Hang on. Hang on! HANG ON!!!” as the band barrels into the opening chords. Harrington’s guitar draws inspiration from the Sex Pistols and Exile on Main Street-era Keith Richards. Sullivan’s distinctive Rickenbacker bass sound is already developing, as is McLain’s brash drumming style. While Heffern is still finding his voice, his lyrics reveal the painful alienation that will later dominate so many of the Penetrators songs: “You walk into that room and you feel those stares/ and everybody wishes that you weren’t there,” he sings on “Vengeance.”

The Penetrators play “Untamed Youth.” Listen now!

The EP they recorded, featuring the songs “Untamed Youth,” “Vengeance” and “Be American,” is youthful, energetic and aggressive, a perfect snapshot of an evolving garage band. It was released on M.R. Records (Monty Rockers Records) at the end of 1978. By that time, the Penetrators had a new guitarist.

Read the full Penetrators story!

— Ray Brandes

Photos and flyers used courtesy of Chris Sullivan and Joe Piper.

Also by Ray Brandes: